Table of Contents

Download/view PDF | PDF for printing

Acknowledgements

This report is based on a study of three California counties’ vote-by-mail programs conducted by the California Voter Foundation. The study was undertaken in partnership with the Future of California Elections (FOCE), a collaboration between election officials, civil rights advocates and election reform advocates to examine and address the unique challenges facing the State of California’s election system.

The California Voter Foundation (CVF) thanks FOCE and its members and staff for their input and support throughout this study. CVF particularly wishes to thank Santa Cruz County Clerk-Recorder Gail Pellerin, Sacramento County Registrar of Voters Jill LaVine and Orange County Registrar of Voters Neal Kelley and their staff members who provided invaluable information and access to CVF in conducting this study. CVF is also grateful to Richard Stewart of the U.S. Postal Service/Pacific Area staff and Darren Chesin, Senior Consultant to the California State Senate Elections Committee, for their assistance. Thanks also to Mary Casey for creating the study banner and to Kevin English for creating the envelope image photograph.

This report is supported by a grant from The James Irvine Foundation. The opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of The James Irvine Foundation.

Credits

Research, writing and graphics:

Kim Alexander, California Voter Foundation president and founder

Saskia Mills, California Voter Foundation research consultant

Technical support:

John Jones, California Voter Foundation technology consultant

1. California vote-by-mail history

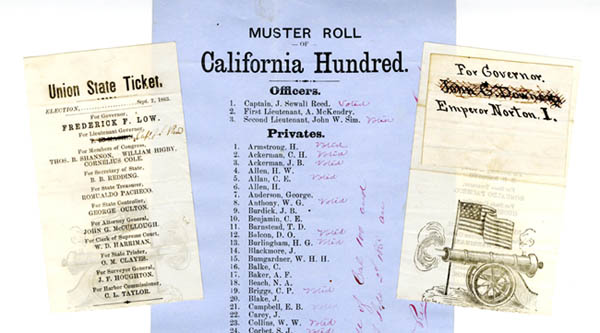

Originally introduced in the 1860s as a way to give California Civil War soldiers the ability to participate in elections, voting by mail was a restricted option in California up until 1979, when a new state law took effect allowing “no excuse” absentee voting. (1) This meant voters could choose to vote by mail if they wished and no longer needed a reason such as illness or plans to be out of town.

|

Images of California Civil War soldiers' absentee ballots and a portion of the muster roll identifying which soldiers had cast absentee ballots. Image collage provided courtesy of the California State Archives. |

In 2002, California law changed again to permit Californians to become permanent vote-by-mail (VBM) voters, allowing all Californians to exercise this option in every election without needing an excuse or having to request a VBM ballot for each election. (2) Another law passed in 2007 renamed “absentee voting” to “vote by mail”. (3)

In the twelve years since enactment of the permanent vote-by-mail law, California’s vote-by-mail rate has steadily increased, topping 50 percent in November 2012, which marked the first time a majority of voters cast VBM ballots in a statewide general election. The ranks of permanent VBM voters have also swelled and now account for 43 percent of all registered voters, totaling nearly eight million California voters. (4)

2. About this study

With the rise of vote-by-mail voters has also come an increase in the number of VBM ballots that go uncounted, due primarily to arriving too late, a lack of signature or the signature provided not comparing adequately to the one on file. The permanent nature of VBM voters also conflicts with the mobile nature of Californians generally; people who live in California move around frequently, creating registration and administrative challenges for voters and election officials alike.

To better understand how California’s vote-by-mail process is working and to identify ways it can be improved to increase the VBM ballot success rate, the California Voter Foundation undertook a year-long study of three California counties and their VBM systems. The three chosen – Orange, Sacramento and Santa Cruz – are of varying sizes but all share a desire to improve their systems and maximize voter participation.

In conducting this study, CVF sought answers to the following questions:

-

Of all the VBM ballots received in recent elections, how many were not counted and why?

-

What are the main reasons VBM ballots go uncounted?

-

What are the procedures for adding and removing voters to and from the permanent VBM voters list?

-

What is the budget for the VBM program and what costs, if any, are reimbursed by the state?

-

What is the VBM program portion of the overall county election budget?

-

What is the county’s relationship with the local post office?

-

What are the postage costs for voters and for county election offices and what is the impact of insufficient postage?

-

What are the various ways/opportunities provided to VBM voters to return their ballots and what is the use rate of these methods?

-

What is the effectiveness and use of online lookup tools that allow voters to check the status of a VBM ballot and the costs/benefits of providing such tools?

-

What are the methods used for processing and verifying VBM ballots and what is the impact of manual vs. automated verification processes including cost, staff time and resource needs?

-

Do the signature verification procedures provide an opportunity for counties to contact voters to correct their ballots prior to the election in order to be counted?

-

What outreach efforts are made to voters whose VBM ballots do not get counted and what is the outcome of these efforts?

Through surveys, site visits, and interviews, and by gathering extensive data from each county, CVF was able to identify a number of areas where the vote-by-mail process appears to be working effectively in the three counties studied as well as areas in need of attention.

Given the widespread use of vote-by-mail ballots, it is essential to review the process as it is currently operating and determine ways to maximize balloting success and reduce disenfranchisement. Enacting legislative and administrative changes as well as improving voter education can help reduce VBM balloting problems and increase voter turnout. To that end, the study concludes with a number of recommendations lawmakers and election officials could implement to improve California’s vote-by-mail process, as well as topics worthy of additional study.

3. Background: Who are vote-by-mail voters?

California voters have a number of choices when it comes to casting their ballots: they can vote at their local polling place; they can vote early at their county election office; or they can cast a vote-by-mail ballot and return it either through the mail or in person to any polling place in their county on Election Day. Voters in California become vote-by-mail (VBM) voters for a number of reasons, usually by choice but also sometimes because circumstances beyond their control force them to cast ballots through the mail.

California law allows any eligible voter to request a one-time VBM ballot, an option voters take advantage of when they know they will be out of town on Election Day, are too busy to get to the polls, or otherwise wish to cast their ballots by mail in a particular election. California voters also have the right to request permanent VBM status. Permanent VBM voters automatically receive a VBM ballot for each election, unless they do not vote in four consecutive statewide elections, in which case they are removed from the permanent VBM list (but not from the voter registration rolls).

Sometimes voters have no choice but to be a VBM voter. County election officials have the power to designate precincts in which 250 or fewer voters reside as mail ballot precincts in which no polling places are set up and all voters residing in that precinct must cast vote-by-mail ballots. For example, in the November 2012 election in Santa Cruz County, approximately 9 percent of the VBM ballots received by the county were cast by voters in mail ballot precincts. Additionally, two of California’s most remote and least populated counties, Alpine and Sierra, are entirely mail ballot counties. Overseas citizens and those in the military stationed away from their home are also required by circumstance to vote by mail.

A study recently undertaken for the Future of California Elections (FOCE) project by the UC Davis California Civic Engagement Project (CCEP) found significant racial, ethnic, political, regional and age disparities among California polling place and VBM voters. (5) Although California's statewide VBM voting rate rose to just above 50 percent in November 2012, in some counties the rate was much higher (Napa, for example, at almost 90 percent) or much lower (Los Angeles at 30 percent) than the overall statewide rate.

VBM voters on average are older than polling place voters, and in terms of political party affiliation are slightly more likely to be members of the Republican Party. While use of VBM balloting by Latino voters increased in 2012, the rate of VBM ballot use by Latino voters is still below average. Asian voters, on the other hand, cast ballots by mail at a higher than average rate.

As Mindy Romero, author of the FOCE/CCEP study notes, understanding the demographics of California's VBM voters is important because "outreach, education and services to VBM voters, or future VBM voters, need to be targeted to reflect the different group use rates."

4. The problem of uncounted vote-by-mail ballots

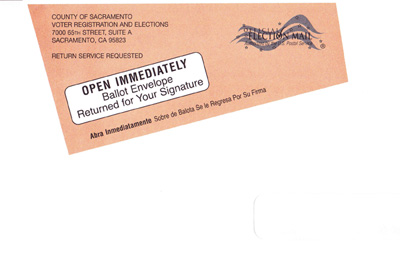

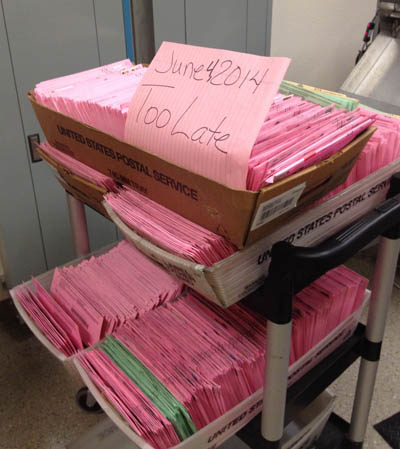

Increasingly, more Californians are choosing to cast a vote-by-mail ballot. Voters can sign up through the voter registration application, and can also now apply online to register to vote. But many of those voters move, and increasingly voter signature images on file with county election offices do not adequately compare to those on vote-by-mail ballots. Many voters fail to sign the VBM envelope, or ballots arrive too late to be counted. After every election, there are piles of vote-by-mail ballots in county election offices that cannot be counted primarily for these reasons. There are a few other reasons, but these three – missing signature, signature does not compare to the one on file, or the ballot arrived too late to be counted – account for almost all of the VBM ballots that went uncounted in CVF’s three-county study.

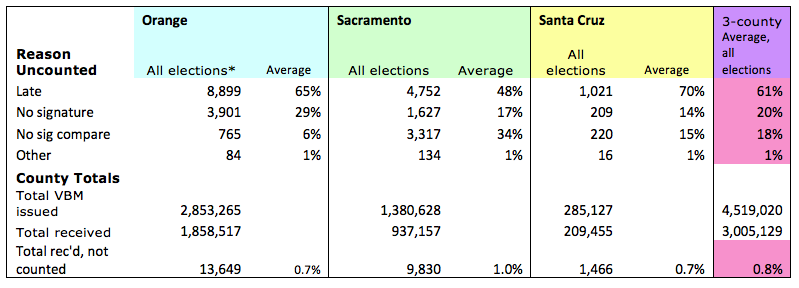

CVF collected and analyzed uncounted ballot data in Santa Cruz, Sacramento and Orange counties over four statewide elections: the 2008, 2010 and 2012 statewide general elections and the 2012 primary election. CVF’s research found that on average:

-

In Santa Cruz and Orange counties, 99.3 percent of VBM ballots cast were counted; and

-

In Sacramento County, 99 percent of VBM ballots cast were counted.

Of the nearly 25,000 VBM ballots cast that were not counted, across the three counties on average:

-

Ballots arriving too late comprised 61 percent of the uncounted ballots;

-

Ballots lacking a signature accounted for 20 percent, and;

-

Ballots with signatures that did not adequately compare to the one on file accounted for 18 percent. (6)

|

* "All elections" includes November 2012, June 2012, November 2010, and November 2008. |

Each counties' uncounted vote-by-mail rate was determined by dividing the number of uncounted ballots by the total number of VBM ballots received (including those received and counted, and those received and uncounted) to arrive at a percentage reflecting how many VBM ballots were not counted of all VBM ballots received. The Pew Center on the States takes a different approach, dividing the number of VBM ballots that went uncounted by the number of all ballots cast in a state - VBM and polling place alike.

Compared to other states, California’s VBM ballot rejection rate is among the highest, according to the Pew Center on the States’ Election Performance Index. (7) Unsuccessful VBM ballots comprised 0.7 percent of all ballots cast in California’s 2010 general election and 1 percent in 2008. The state’s performance in this area improved in 2012, when Pew reported a 0.5 percent California VBM rejection rate, but it is still considerably higher than most other states.

Comparing Pew’s findings with actual turnout results, one can estimate that:

-

In November 2008, approximately 137,000 California VBM ballots cast were not counted;

-

In November 2010, approximately 72,000 VBM ballots were not counted, and;

-

In November 2012, approximately 66,000 VBM ballots were not counted.

In CVF’s three-county analysis, uncounted VBM ballots accounted for 0.47 percent of all the ballots cast in all three counties across the four elections studied:

One of the most significant reasons VBM ballots go uncounted is late arrival. Under current California law, VBM ballots must be received by the close of polls on Election Day in order to be counted; unlike a tax return, Election Day postmarks don’t count. Research conducted for this report, along with research published by the Public Policy Institute of California (PPIC) (8), shows that while the number of late ballots is low relative to the total number of VBM ballots cast, late return is either a major reason or the number one reason VBM ballots are not counted in many California counties and was the number one reason for uncounted ballots in all three counties CVF studied.

A bill pending in the California Legislature, Senate Bill 29, would change California law to allow ballots postmarked by Election Day and received within three days of Election Day to be counted. (9) PPIC’s study shows that the overwhelming majority of ballots returned late were received by election offices within three days of Election Day. It is likely enactment of SB 29 would result in a significant decrease in the number of uncounted VBM ballots.

III. County Profiles

IV. Findings

1. How does a voter get on or off the permanent VBM list?

State law allows voters to become permanent VBM voters if they wish, a choice that can be made by: completing a voter registration form and checking the “Permanent Vote-by-Mail voter” box; completing a VBM application included in the county sample ballot; completing, printing, signing and mailing a print or online VBM application from the county or the Secretary of State; or, requesting permanent VBM status via written correspondence with the county. None of the three counties whose practices were examined do any special recruitment of permanent VBM voters outside of providing information about the option in routine mailings and on the counties’ election websites.

In all counties, voters on the permanent VBM list who do not vote after four consecutive statewide general elections are by law removed from the permanent VBM list. (10) Because the law is silent on the issue of how voters can voluntarily remove themselves from the permanent VBM list, various methods exist depending on the county. Sacramento County, for example, does not have a form for requesting removal from the permanent VBM list, and its website does not address the issue of how to remove oneself from the list. In Sacramento, voters typically contact the elections office by phone to start the process of removal from the permanent VBM list. In Santa Cruz County, voters can remove themselves by sending a written request or, in some cases, by calling and providing information over the phone. Neither county requires a voter’s signature to remove him or herself from the permanent VBM list. Orange County has a form specifically for this purpose, which it makes available to voters through the mail, at the election office or online. Applicants using the online form fill out several fields and then, after hitting “submit” those fields pre-populate a form letter addressed to the Registrar of Voters including a required signature field. The county also accepts written requests without the form submitted via mail, fax or in person. Because of the easily accessible information on its website and form designed specifically for this purpose, Orange County's practices are an excellent model for other counties wishing to provide clearer direction to its voters on this topic.

State law regarding removal of permanent VBM voters from the VBM list has changed several times in recent years, making it somewhat challenging for election officials to keep their notices to voters current and up-to-date. CVF’s study of the three counties as well as a handful of others examined found inconsistencies in messaging to voters on this issue, with some counties stating voters would be removed from the permanent VBM list after failing to vote in two consecutive statewide elections and others correctly stating the law as four statewide elections.

2. Permanent vs. one-time vote-by-mail voters

Data collected for this study reveal that in the three counties studied, turnout of permanent vote-by-mail voters is consistently lower in every election than that of one-time vote-by-mail voters, ranging anywhere from 2 percent to 35 percent lower depending on the particular county and election.

In two counties – Orange and Sacramento – the smallest difference between turnout of permanent and one-time VBM voters came in the November 2008 presidential election (which was a high turnout election). In Sacramento County the difference between turnout of permanent and one-time VBM voters in that election was 6.6 percent, and in Orange County it was 9.6 percent. Santa Cruz County's smallest turnout gap between permanent and one-time VBM voters came in the November 2012 election, when the difference was just 2.4 percent.

Many voters choose to sit on the sidelines during primary elections; regardless of their participation plans, however, all permanent VBM voters are issued ballots. A one-time VBM voter must proactively request a mail ballot just weeks before an election and thus is likely to be anticipating its arrival. By comparison, a permanent VBM voter who has not requested a ballot may be less aware that an election is approaching and therefore less likely to be keeping an eye out for an arriving ballot.

As a result, a low turnout rate of permanent VBM voters as compared to one-time VBM voters is especially pronounced in primary elections, when overall turnout is typically lower than in general elections. In all three counties, the biggest difference between turnout of permanent and one-time VBM voters showed up in the June 2012 primary. (11) In that election, the gap between turnout of permanent and one-time VBM voters was 22.4 percent in Orange County, 25.6 percent in Sacramento, and 34.8 percent in Santa Cruz.

3. Issued vs. returned vote-by-mail ballots

One clear consequence of giving voters the right to become permanent vote-by-mail voters is that many people who do not intend to vote are still sent a ballot, resulting in higher costs for the counties and potential election security problems, with as many as several million VBM ballots failing to connect with voters each election.

The chart below shows how many VBM ballots were sent to voters by the three counties in June 2012 compared to how many were returned:

Because California law currently states that county election offices shall remove voters from the permanent VBM list only after they have failed to vote in four consecutive statewide general elections, an inactive voter will automatically receive mail ballots for all local and state elections for eight years before they are no longer sent a VBM ballot. While this provides convenience to the voters, it increases election expenses by automatically sending ballots out to people who may have no desire to vote in every election.

4. Vote-by-mail administrative costs

Each of the three counties reported their overall election costs for 2012 as well as the cost of their vote-by-mail operation. VBM costs typically include the production and mailing costs of VBM ballots, identification envelopes and instructions; equipment leasing and maintenance; staff time and oversight required to process ballots and assist voters; handling of receipt of VBM ballots at polling places; and processing, verification and counting.

However, comparing these costs across counties can be difficult, primarily because categories of costs are not uniform across all counties. One county may have to pay to lease office space, for example, while another gets its space for free. One county’s general fund may benefit from greater tourism or tax revenues than another, resulting in more funding opportunities for one county’s election office compared to another’s. Another difficulty in assessing election costs is that those costs can vary greatly from year to year depending on whether there is one election, several elections or no elections.

Below is a summary of what each county reported spending on its vote-by-mail program in November 2012 and its overall election budget for the same year:

-

Orange: VBM costs: $429,295 / Election budget: $5,364,484

-

Sacramento: VBM costs: $921,324 / Election budget: $6,112,847

-

Santa Cruz: VBM cost: $140,000 / Election budget: $2,488,371

It is noteworthy that while Orange is home to almost twice as many VBM voters as Sacramento, its VBM costs and budget are smaller. This is likely due to the fact that Orange, as a larger county, has greater access to capital that has allowed the county to make large-scale equipment purchases and brought the production of its VBM materials in-house, thus eliminating the need to pay vendors for such services. The county also benefits from an enormous warehouse space that can house its election administration equipment and operations on-site.

Regardless of variations in program costs, Orange, Sacramento, Santa Cruz and all other California county election departments are entitled to reimbursement from the State of California for operating vote-by-mail programs, as required by the California Constitution. (12) However, beginning with the 2011-2012 state budget, California Governor Jerry Brown and the State Legislature began withholding funding in the state budget to pay for state-mandated local programs, including programs enacted by the Legislature to expand opportunities to vote by mail. Below are the nine unfunded election program mandates, along with the estimated amount each item would cost if it were to be funded in the 2014-15 state budget: (13)

1. Absentee Ballots (Ch. 78 of 1977) – $49,422,000

2. Absentee Ballots – Tabulation by Precinct (Ch. 697 of 1999) – $68,000

3. Brendon Maguire Act (Ch. 391 of 1988) – 0

4. Fifteen Day Close of Voter Registration (Ch. 899 of 2000) – 0

5. Modified Primary Election (Ch. 898 of 2000) – $1,738,000

6. Permanent Absent Voters (Ch. 1422 of 1982) – 0

7. Permanent Absent Voters II (Ch. 922 of 2001) – $6,560,000

8. Voter Identification Procedures (Ch. 260 of 2000) – $7,553,000

9. Voter Registration Procedures (Ch. 704 of 1975) – $2,481,000

As the list shows, vote-by-mail programs comprise the largest portion of the unfunded, state-mandated election programs. It is the official position of the State of California that when funding for state-mandated programs is withheld, counties have the option to suspend those programs if they wish. To date, no California county has stopped offering vote-by-mail options to its voters. The risk remains, however, that a county or several counties could suspend vote-by-mail services because they are not receiving state funds to support the state-enacted and state-mandated vote-by-mail programs.

Due to this risk, the state’s nonpartisan Legislative Analyst’s Office has recommended since 2013 that the election mandates funding be restored. In its analysis, the LAO wrote:

The state has a significant interest in maintaining uniformity in its elections. Many of the state’s elected officials serve districts that span multiple counties. Variation in election policies among those counties would result in voters in the same district having access to different voter programs. In a single state Senate district, for example, voters in one county might be allowed to vote absentee while voters with identical circumstances in an adjacent county may be denied an absentee ballot. Thus, suspending elections mandates could lead to inconsistencies in elections, voter confusion, and possibly lower turnout.

Suspending elections mandates poses a significant risk to state elections. Specifically, the longer the state suspends these mandates and the more elections mandates the state chooses to suspend, the greater the risk that at least one county will decide not to perform the previously mandated activities. Accordingly, we recommend that the Legislature fund these mandates in the budget bill. (14)

While the amount needed in the current budget to restore the funding to pay for election programs is relatively small ($100 million to cover current and recent years of suspended mandates) given the size of the entire state budget – $156 billion – the amount is significant in the eyes of county election officials who are now providing programs with fewer resources. For Sacramento County, the amount no longer being reimbursed by the state represented about 10 percent of the county’s entire 2012 annual election budget. Consequently, other services or conveniences may suffer, such as extending office hours to voters the weekend prior to the election or opening up early voting centers.

5. Relationship with the U.S. Post Office

A key but frequently overlooked participant in the vote-by-mail process is the U.S. Postal Service, upon whom voters and election officials alike rely to facilitate most VBM transactions. The level of sophistication a county is able to bring to its mailing operation and relationship with the U.S. Post Office varies greatly depending on the size of the county election office’s budget and staff. CVF’s three-county study found that the largest county studied, Orange, had the capacity to bring many mailing house operations and functions in-house, while the other two counties studied, Sacramento and Santa Cruz, rely on outside vendors to produce and send out election mail.

One challenge that postal workers face in delivering election mail is that they receive contradictory messages. On the one hand, “revenue protection” is a key goal of the USPS that postal workers are reminded of frequently by their USPS supervisors and throughout their training: if a piece of mail doesn’t have the full postage due on it, postal workers are tasked with collecting that revenue. On the other hand, when it comes to election mail, the official policy is to “send it through” even if the envelope is lacking any or sufficient postage. (15) And while all three counties studied maintain accounts with their local post office to cover insufficient postage, many postal employees from other states or even countries are also responsible for handling election mail. These non-local employees are also responsible for upholding the “revenue protection” mandate and may be unaware that California counties will cover postage due costs.

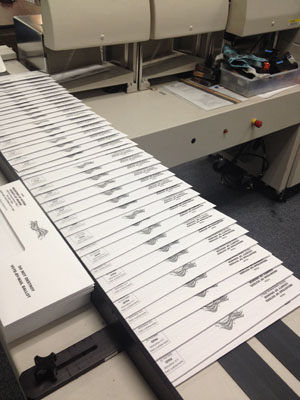

|

Orange County's in-house mail processing equipment automatically labels envelopes and inserts ballots. |

Orange County prepares its own sample ballots and VBM ballots for mailing, which in many counties is a task that gets outsourced. Because Orange does this itself, in the eyes of the post office it is considered a large mailer and therefore is able to take advantage of cost-saving options unavailable to counties with smaller mailing operations.

After undertaking an examination of the entire election mailing operation, including identifying slow points in the mailing and postal operation and researching how large mail contractors set up their operations, Orange County's Registrar of Voters Neal Kelley established what amounts to an in-house post office to handle the county's election mail.

Kelley rents necessary equipment that otherwise would be provided by the post office itself, including a large scale for weighing pallets of mail, and uses trucks the election office owns to deliver them to the regional postal facility. Election office staff facilitate automated addressing and preparation of all the mail and then work closely with postal employees who come to the election warehouse to handle paperwork that normally has to be dealt with at the post office's bulk mail counter. Postal employees oversee delivery of the ballots directly from the election warehouse to a regional distribution center.

In spite of the advantages provided by this unique arrangement, Orange County is not immune to hiccups involving the post office’s processing of VBM ballots. For example, in a recent election there was an incident in which a number of military/overseas ballots being mailed out by the election office were returned to the county due to "insufficient postage", when no postage at all is required on military/overseas ballots (a fact that is noted on the front of the envelope itself.)

In this case, the problem was traced to a particular individual who was handling the ballots incorrectly. While the post office was responsive and a manager assumed oversight of military mail for the rest of that election, it was still an egregious example of improper handling of election mail by the post office.

The post office is informed that the Registrar of Voters office will pay postage due when ballots have been returned by voters with insufficient postage, and it does normally forward such ballots to the county. This cooperation between the county and post office helps prevent disenfranchisement caused by delays in receiving ballots, and costs the Registrar's office only a small amount of money each election.

While Kelley notes that the election unit at national post office headquarters has been very responsive to concerns of election officials, he also believes a campaign to education all postal workers about the importance of sending election mail through to election offices is warranted.

Sacramento County maintains a close relationship with the main Sacramento post office and local post office branches, communicating throughout the year about election schedules and cooperating on Election Day night to make sure no ballots have been overlooked at the postal facilities.

Sacramento outsources the printing and mailing of sample ballot pamphlets and VBM ballots. Recently, the county has contracted with two different vendors for the two types of mailings. As is the case in Orange, Sacramento County covers the cost of postage due on any ballots that were mailed with insufficient postage, which is normally $500 or less for statewide elections.

One issue of concern found in Sacramento County (which may exist in other counties as well) involves difficulties experienced by some voters in all vote-by-mail precincts. Those voters' ballot return envelopes are postage paid, which could be considered an advantage to voters; however, it means the ballot must go through the business reply unit of the post office in order to be canceled against the county's business reply account. When only one person works in the business reply unit, mail can be delayed if that person is out of the office or if there is a surge of business reply mail from other sources, possibly disenfranchising a voter who waited until close to the election to return his or her ballot.

Taking a closer look at these ballots, CVF found that in Sacramento County in November 2012, a total of 6,618 ballots from all mail precincts were received and counted, while 227 ballots from mail precinct voters were rejected, resulting in a 3.3 percent uncounted rate, which is more than three times higher than the 0.9 percent uncounted rate for all vote-by-mail voters in that election. Ballots rejected in this group for arriving too late comprised 81 percent of all the uncounted ballots – nearly double the late ballot rejection rate countywide for the same election, which was 45 percent. Researchers concluded that while voters casting VBM ballots in all vote-by-mail precincts have the right to save the cost of postage, they might better ensure the timely delivery of their ballot by paying first class postage and avoiding potential business account processing delays.

US. Postal Service budget cuts and facility consolidation have taken a toll on Santa Cruz County and its VBM voters. The county’s mail is processed in neighboring counties – either in San Jose, located in Santa Clara County, or Oakland, located in Alameda County. Out-of-county processing appears to cause more delays and more late ballots for Santa Cruz compared to the other two counties studied and may explain why this county’s late ballot rate was the highest among the three counties studied.

However, Santa Cruz County's election office staff report a strong working relationship with their local post office's main branch, and they enter all election mail through that branch rather than through the main district office in San Jose.

Like Sacramento, they work with the post office in establishing the mailing schedule. Santa Cruz sends samples of VBM envelopes to post office area managers ahead of the election, in order to alert them to what the mail pieces look like and help prepare postal workers to handle important election mail in a timely manner.

In case there are problems with outgoing mail, Santa Cruz election staff photograph examples of the outbound sample ballot and VBM ballot packets, so they have a record of the barcode and can provide the post office with that information if they hear of delays from voters in receiving election mail.

This procedure came in handy when one of the county’s own election staff members had a problem with delivery of her VBM ballot and used the photographs of the election mail bar codes to help solve it. In that case, her ballot and those of other voters in her neighborhood were mistakenly put in a cart labeled "hold" in the San Jose district office, in spite of being tagged as election mail. It took 18 days for the VBM ballot to get to her. This happened just eleven days prior to Election Day, and the staff member ended up hand-delivering replacement ballots to a number of voters. It took a considerable amount of staff time to determine the fate of the misplaced ballots, and the pictures of the bar codes were key to helping solve the mystery.

6. Postage Costs

For outgoing mail, each of the three counties studied takes full advantage of nonprofit bulk mailing rates offered by the U.S. Postal Service in order to achieve savings on mailing costs.

The cost to return a VBM ballot can vary dramatically. VBM ballots and envelopes vary in size and weight depending on the county’s ballot style and the number of contests on a voter’s ballot. Longer ballots weigh more and require extra postage.

All three counties have postal accounts to cover additional postage costs (though they don’t advertise it). The “postage due” costs were relatively minimal in all counties, typically amounting to a few hundred dollars in a major election. While some have suggested providing postage-paid envelopes to all VBM voters (and not just those overseas or living in an all vote-by-mail precinct as current law provides), doing so can actually delay VBM ballot processing since postage paid mail is typically sent business class, not first class. In addition, the cost must be debited from the account holder before the mail piece can be delivered. Ensuring postage-paid mail is debited from the correct account adds extra time to ballot processing and can further delay the return of voted ballots.

Santa Cruz has found that its VBM ID envelope (with a ballot inside) has in recent elections cost a voter anywhere from $.46 to $.61 to return to the county. The problem is that the sample envelopes – all with the same exact material inside – will end up weighing slightly different amounts depending on which post office meter is used and which postal worker is doing the weighing. The variation is likely due to lack of calibration or even weather conditions. The weight determines the amount of postage required, which Santa Cruz writes into the VBM instructions to voters.

To further study this problem, CVF took a June 2014 Sacramento County vote-by-mail envelope, with a ballot inside, to a neighborhood post office to have it weighed. The ballot and envelope reportedly weighed one ounce and would cost $.49 to mail. After requesting it to be weighed by a different postal worker on a different scale in the same post office, it was found to weigh two ounces and would cost $.71 to mail.

To prevent voters' ballots from being refused for insufficient postage due to this problem, the Santa Cruz election office instructs voters to pay the highest postage rate quoted by postal employees. The county also has an account to pay for any insufficient postage. Santa Cruz has found this solution works well most of the time, but in spite of the strong relationship and education of postal workers, a very small amount of election mail does sometimes still get returned to voters due to lack of postage.

Santa Cruz election officials note that confusion around the postage required on a VBM ballot is enhanced by the fact that for voters in all-mail-ballot precincts, postage is paid by the county, but for voters who choose to vote by mail, postage must be paid by the voter.

7. Timing of delivery of ballot materials

In a statewide election, a vote-by-mail voter receives three mailings from state and local agencies: the state Voter Information Guide (VIG), sent to all registered voters by the Secretary of State; the county sample ballot booklet, sent to all registered voters from their county election office; and the vote-by-mail ballot, envelope and instructions, also sent from the county office.

Ideally, voters would receive their information guide and sample ballot booklet prior to receiving their VBM ballot. Counties try to sequence their election mail so the sample ballot book, with information about many of the candidates and local measures on the ballot, is received by voters before VBM ballot materials are received. But the timing of these deliveries cannot always be controlled.

As Sacramento Registrar Jill LaVine pointed out, the sample ballot books are subject to court challenges, and if those occur the county affected will get placed “at the back of the line” with their printing vendor, who is likely also printing election materials for other counties operating under the same deadline pressures. Sample ballot production and mailings can also be delayed by late receipt of candidate information from the Secretary of State’s Office or late receipt of translations.

In addition, different vendors may handle the two county mailings, possibly relying on different contacts within different post offices to send out the mail, which can make it challenging to coordinate the timing of election material delivery. Complicating this matter further is the state VIG, which contains extensive information about state propositions as well as some candidate information and voting tips and instructions; the delivery of this guide is not currently coordinated with county registrars.

Occasionally, the State Legislature places a measure on the ballot after the state guide has gone into production. When that happens, the Secretary of State prepares a Supplemental Voter Information Guide, which typically arrives after the VIG and may show up after some VBM voters have already cast their ballots.

Orange, Sacramento and Santa Cruz Counties all mail VBM ballot materials to voters approximately 29 days prior to the election, which ideally is one to two weeks after voters have received their sample ballots. With its in-house mailing operation, Orange County has greater control over timing and coordination of mailings to VBM voters than Sacramento or Santa Cruz.

In Santa Cruz County, VBM ballots all enter the post office at the same time, whereas sample ballot pamphlets enter over the course of six days depending on zip code, creating a situation in which it's possible for some VBM voters to receive their ballots a day or two before receiving their sample ballot pamphlets. Santa Cruz County’s ability to predict the timing of when ballot materials will be delivered is hampered by the fact that the county’s election mail is processed in neighboring counties before returning to Santa Cruz for delivery.

8. Instructions for voters

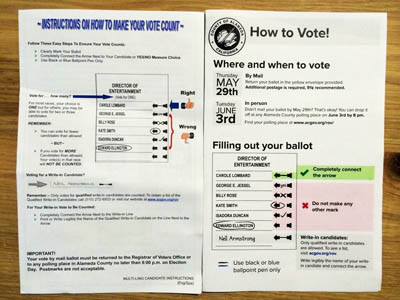

|

Santa Cruz County's vote-by-mail instructions. Click here for a larger image. |

All three counties mail instructional handouts to voters who vote by mail. In addition, California law requires a number of notices to appear on the VBM envelope. All counties provide VBM instructions on their websites during elections as well, though not always year-round.

Two of the counties studied have worked to improve their VBM materials by conducting a “plain language” review. These reviews have resulted in the use of more graphics and white space in the materials, making them easier to read.

The issue of vote-by-mail instructions received some extra attention in the June 2014 primary, when a California voter who also specializes in information design took the initiative to voluntary redesign her county’s instructions. The voter, Molly McLeod, is also a Code for America Fellow and posted a blog about her redesign. (16) The “before and after” picture and narrative that accompanied it were widely shared through social media and provide an excellent example of how redesigning election information can improve voter education.

|

A California voter's volunteer effort to redesign Alameda County's vote-by-mail instructions. Click here for a larger image. |

9. Vote-by-mail ballot envelopes

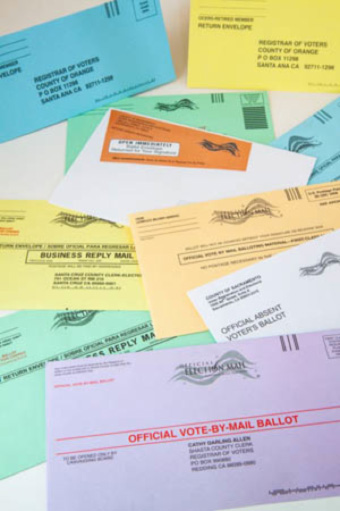

|

A collage of county vote-by-mail envelopes. Photo credit: Kevin English. |

The envelopes used by voters to return their VBM ballots, called identification (ID) envelopes by elections officials, vary in terms of the text and graphics included on the envelopes, the color of the paper, and handling of the voter's signature. Envelopes come in a rainbow of colors, include required and optional text, and deal with signature privacy differently.

Most feature rather small print and a lot of instructional text on the back. Envelopes vary not only from county to county, but also within a particular county depending on the election the envelope is being used in, and which type of voter is receiving the envelope. County officials report that using different colored envelopes helps agency staff better track ballots when conducting more than one election simultaneously, such as a countywide election and a special election. The use of differently-colored envelopes also helps election officials more easily identify ballots coming from military/overseas voters and all mail ballot precinct voters.

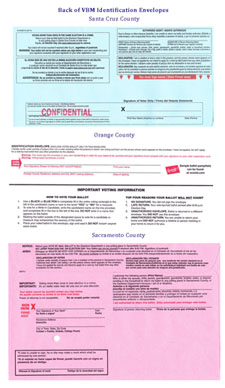

As noted above, California law requires several disclosures to be made on vote-by-mail envelopes. As a result, the envelopes can appear to be quite cluttered and difficult to read, with text featured in small font and all-capital letters. Examples of the back sides of the standard VBM envelopes used by the three counties studied are featured below.

In Santa Cruz County, all VBM ballots are sent out to voters in white envelopes. Ballots are returned in ID envelopes of various colors that are uniquely coded to each voter. Blue envelopes are standard, green envelopes are used only in all-mail precincts, white are for overseas citizens and military, and yellow are used in special elections. On most, signing instructions and the text "OFFICIAL VOTE-BY-MAIL BALLOT" are in red font. Though ID envelopes are linked to individual voters, all counties reported that they will still count the ballots of spouses or household members who accidentally switch envelopes, as long as both ballots and ID envelopes turn up during the count.

|

Examples of the back sides of the three counties' vote-by-mail envelopes. Click here for a larger image. |

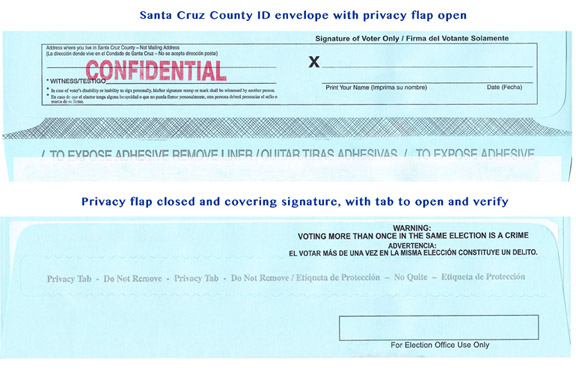

After receiving some complaints about the lack of privacy of voters' signatures, Santa Cruz County changed to envelopes with privacy flaps. The envelopes work by allowing the voter to sign the ID envelope and then fold an opaque flap over the signature, sealing it just below the signature itself; elections staff can then pull a tab to reveal and check the signature, leaving the ballot sealed in the envelope. Such envelopes simultaneously protect the privacy of a voter's signature and allow that signature to be checked in a timely way, prior to the point of actually opening the envelope and removing the ballot, which cannot happen under state law until ballots are ready to be processed and counted once the polls close on Election Day.

In Sacramento County, pink envelopes are the standard color used for returning VBM ballots, while yellow envelopes are used for military and overseas voters, and green envelopes are used for voters in all vote-by-mail precincts. Both the green and yellow envelopes are “postage paid” while the standard pink envelope requires postage. A limited amount of text on both envelopes is in red font. All of the envelopes say either "OFFICIAL MAIL BALLOT" or “OFFICIAL VOTE-BY-MAIL BALLOT” on the front. Sacramento has had some complaints about the lack of privacy of voters' signatures, but changing to an envelope with a secrecy flap is cost prohibitive because it would require the use of different ballot processing equipment. Voters concerned about signature privacy are directed to put their ID envelope inside another envelope before mailing it.

|

The top image shows what Santa Cruz County's envelope looks like with the privacy flap open; the second image shows what it looks like once sealed. The privacy tab is removed by election workers, allowing them to inspect the signature without opening the envelope. |

Orange County also uses different colored ID envelopes for different elections and types of voters. Its standard envelope is white with both black and red font; other colors are used for special elections. In the past, Orange County's envelopes have not included the "Official Election Mail" logo featured on both the Sacramento and Santa Cruz envelopes, but that is reportedly changing. The graphic, while not required, does help signal to postal workers that they are handling time-sensitive election mail. Also unique to the standard Orange County envelopes is that they include instructions on "How to Vote Your Ballot", which were added after the county found that people often don’t read the instructions included in the VBM packet, and also a list of the "Top Four Reasons Your Ballot Will Not Count".

|

The United States Postal Service's "Official Election Mail" logo, as it appears on a Sacramento vote-by-mail envelope. |

The variations described above are partly a reflection of the fact that ID envelopes serve subtly different purposes for different audiences. Voters, postal employees, and election officials have different goals and interests when it comes to the election and envelopes: voters are primarily concerned about casting a valid ballot and may be concerned about the privacy of their signature; the post office is concerned with timely delivery of mail, but also has to look out for its own bottom line; and election officials are focused on both increasing turnout and administering elections efficiently and securely.

An example of an envelope feature that is helpful to one audience but not necessarily to others is envelope color. While a statewide, uniform envelope color might give voters and postal workers a consistent visual cue from one election to the next that they are handling a time-sensitive ballot, in practice having different colored envelopes helps election workers organize and sort ballots, and quickly identify ballots that have been mistakenly returned by a voter to the wrong county.

Modifying or improving ID envelopes requires taking into account not only legal requirements, but also the needs of each of the different audiences who use them – voters, election staff and postal workers – which is one reason attempts to change the envelopes can be challenging.

10. Ability to track ballots going out and coming back

Among the three counties whose practices were examined for this study, the ability to track VBM ballots on their way to the voter and on their way back to the election office varies widely. Santa Cruz and Sacramento currently are doing very little tracking, while Orange is on the cutting-edge of VBM ballot tracking.

Orange County was one of the first to implement tracking of individual ballots through the postal system, and does so using a combination of post office Intelligent Mail barcodes and a third party software product called "Track My Mail". Together, those products provide helpful clues as to whether and why some voters' election materials or ballots are being held up during their journey through the postal system.

Since 2012, this setup has allowed Orange County election workers to tell a voter exactly when their mail carrier took possession of their outgoing ballot from the sorting facility, and also to look up a digital image of the outgoing ballot envelope. In 2014, Orange County plans to have full-service Intelligent Mail in place, which will provide even greater ability to track ballots. Sacramento and Santa Cruz counties have not tracked VBM ballots in this way in the past, but Sacramento is hoping to implement full-service tracking of individual ballots soon.

Vote-by-mail ID envelopes being returned by voters in all counties are required to have an Intelligent Mail barcode on them, but that code is used primarily by the post office for sorting and bundling the mail. Counties with tracking software can also use it to track delivery of ballots coming back to the election office from the voter. Upcoming changes in post office requirements relating to the use of Intelligent Mail barcodes (IMb) will likely force improvements in mail tracking for future elections.

Though the post office's IMb coupled with third party software options give election officials unprecedented insight into the movement of ballots through the postal system, it could be difficult at this time for election officials to pass on this knowledge to voters via a real-time online lookup tool, since these tools are provided through the counties’ election management system vendor and have a limited range of interoperability. Counties may want to consider how real-time tracking can be integrated with an online voter lookup tool.

11. Online lookup tools

All three counties examined in this study offer voters online tools for checking their vote-by-mail participation status and VBM ballot status. The tools vary in design, seasonal availability, what data is required to access the information, and the descriptions used to provide voters with information about their status. Usage of the tools also varies, but is hard to compare given that in one county the VBM lookup tool is combined with other functions (i.e. voter registration lookup), and one county does not track usage of the tool at all. All three of the counties' lookup tools lacked information about a voter's VBM voting history at the time of CVF’s review. However, following the review, Santa Cruz revised its lookup tool to provide the voter’s entire voting history.

In Orange County, voters have year-round access to an online VBM lookup tool to confirm whether they are permanent vote-by-mail voters. If they have made a one-time request to vote by mail, it can be confirmed during the current election period for which they requested one-time VBM voter status. After entering date of birth, the last four digits of their driver's license, and verifying the entry with a captcha, voters can determine their VBM voter status, the exact dates their VBM ballot was issued and returned, and whether it was accepted or challenged.

During the research for this study, it was pointed out to Orange County Registrar of Voters Neal Kelley that the terms used in the county's VBM lookup tool – counted ballots are described as "good" and uncounted ballot as "challenged" – were unclear and may confuse voters. In response to that feedback, the county changed the language used in its lookup tool to be more specific. Now, instead of “good” the voter is informed, “Your vote-by-mail ballot has been counted.” Instead of “challenged” it now says “Your vote-by-mail ballot did not count”. Descriptions of the reasons for not counting are:

“Too Late – your vote-by-mail ballot was not received by the deadline.

No Signature – you did not sign your vote-by-mail envelope.

Non-matching Signature – Your signature on your vote-by-mail ballot envelope did not match your voter record signature.

Undeliverable – The Post Office returned your vote-by-mail ballot as undeliverable.”

|

Screen shot of Orange County's online, all-in-one lookup tool. |

Orange County's lookup tool is part of the county's all-purpose "Voter Lookup" portal and is accessible from any page on the website, making it easy for voters to find and utilize. Because the VBM lookup tool is integrated with the main registration lookup, there is no way to track usage statistics specific to VBM status requests. In the 29 days prior to the November 2012 election, the all-in-one tool logged 208,000 page views, possibly indicating that many phone calls or email inquiries that could have been made by voters were not necessary, thus a significant time savings for agency staff.

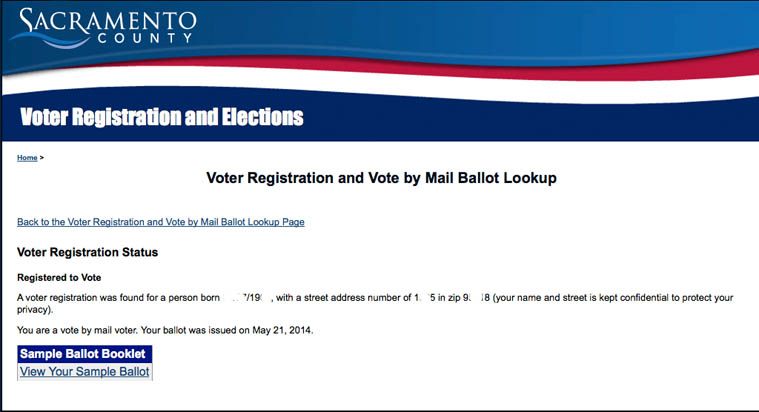

Sacramento County offers a seasonal VBM status lookup tool available during election periods that provides voters with the dates their VBM ballot was both issued and received by the county after being cast by the voter. Voters need to input their street number, zip code and full birth date in order to access their information. The VBM lookup tool is bundled with the registration status tool, providing confirmation to voters of both their registration and VBM status. During elections, the tool also provides a link to the voter’s sample ballot booklet.

Sacramento's lookup tool does not include the voter's name on the return screen; instead there is a note explaining that the name is not visible for the sake of privacy, thus not revealing any more personal information about the voter than was initially entered. (17) The tool also does not provide information about whether the returned ballot was actually accepted or challenged. This detail will likely need to be added in order to meet the requirements of Senate Bill 589, enacted in 2013, which requires counties to provide to voters, upon request, information about why their ballots were not counted.

|

| Screen shot of Sacramento County's vote-by-mail status lookup tool. |

Sacramento County's VBM lookup tool logged approximately 24,000 lookups in the month prior to the November 2012 election, which was about equal to the amount of traffic generated by the county's polling place lookup tool. The county reports it receives very few phone calls from voters inquiring about their VBM ballot status, and therefore feels the lookup tool is effective and worthwhile. The election office removes the VBM lookup tool entirely from its website after the election, due to "limited room on the computer" and in order to reduce voter confusion.

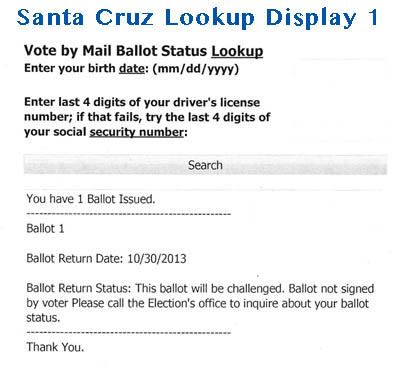

During the course of the study, Santa Cruz revised its lookup tools following a review. Initially, Santa Cruz County offered voters a year-round, online lookup tool that provided voters with VBM ballot status information for the most recent election only. The lookup tool asked for a voter's full birth date and last four digits of his or her driver's license number or Social Security number. It returned confirmation that a VBM ballot was issued, the date it was returned to the county by the voter, and its status.

|

Santa Cruz County's initial lookup tool display providing details about why a vote-by-mail ballot did not get counted. |

A ballot that was returned and accepted was termed "good"; if it was not accepted, there was a note specifying that the "ballot will be challenged", including the reason why (i.e. ballot was not signed.) However, these notes were not visible to voters via online lookup until after the election was over. Instead, prior to the election, a voter whose ballot was being challenged would see a somewhat misleading message stating that the ballot has not yet been processed.

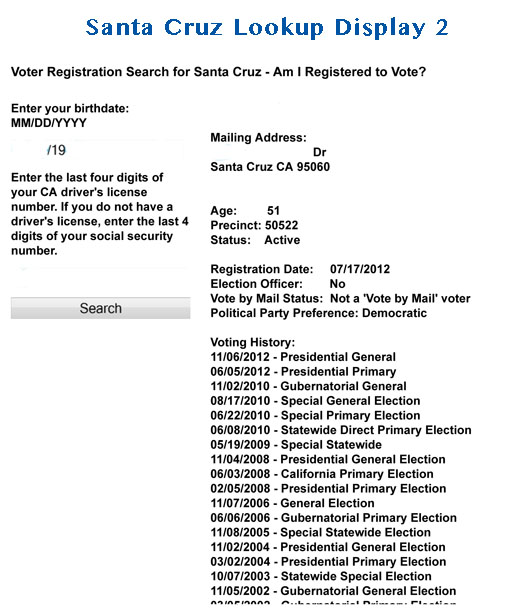

Following CVF’s review, Santa Cruz worked with their election management system vendor to improve their lookup tool messaging, specifically to add contact information and to change the term “good” for accepted ballots to “accepted”. Santa Cruz also modified its lookup tool to create an “all-in-one” lookup tool, similar to Orange County’s, that lets a voter access a variety of information about his or her voter record, including vote-by-mail status, verification of registration status and date, voting history, precinct, and political party preference.

|

Santa Cruz County's expanded lookup tool provides additional information including party preference and voting history. |

In the case of a challenged ballot, the voter was directed to call the election office, though the lookup tool return screen did not include any contact information. Santa Cruz County election administrators reported that they would be looking into adding that information to the tool, and would consider changes to the language used prior to the close of the election regarding challenged ballots.

Santa Cruz County does not compile usage statistics for its VBM lookup tool, but the election office feels the tool is effective, inexpensive, and benefits voters greatly. One minor problem relating to the tool is that some voters who drop off their ballots on Election Day call the day after the election wanting to know why the lookup tool does not reflect their voted ballot status. While some voters are expecting to see their online record instantly updated, the reality is that due to manual processing of the county’s ballots, it can take 48 hours just to record all of them, and the lookup tool is updated just once daily. Voter education and perhaps a revision to the text in the lookup tool display might help address this problem.

12. How vote-by-mail ballots are returned

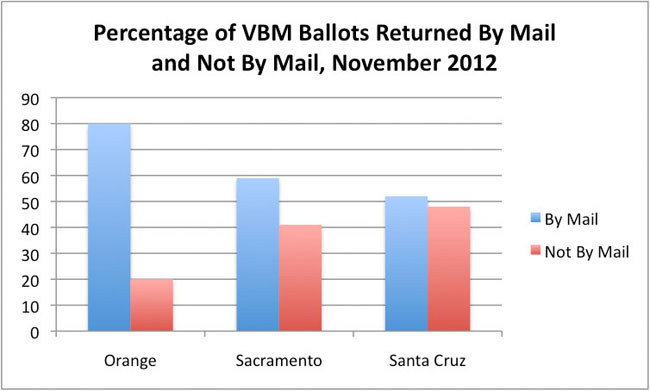

For various reasons, many voters who have elected to receive vote-by-mail ballots – either for one election or permanently – choose to return those ballots using a method other than by mail. Of the nearly one million voters who  returned November 2012 VBM ballots in the three counties examined for this study, approximately 30 percent of them actually voted in person, by dropping off their ballot at the election office, at a drop site, or at a polling place in their county on Election Day.

returned November 2012 VBM ballots in the three counties examined for this study, approximately 30 percent of them actually voted in person, by dropping off their ballot at the election office, at a drop site, or at a polling place in their county on Election Day.

CVF found that two of the three counties studied, Sacramento and Santa Cruz, routinely establish ballot drop-off sites throughout the county where voters can return their voted VBM ballots prior to Election Day. Drop-off sites are typically located in government buildings, such as city halls and public libraries. While these drop-off sites provide additional convenience for voters, particularly those living in geographically large counties, current California law does not actually provide for ballots to be returned to locations other than the county election office or describe when drop-off ballots must be collected and how they will be protected.

In Santa Cruz County, the trend is toward an increasing number of vote-by-mail voters not actually returning their ballots via the mail. Whereas in November 2008, 60 percent of Santa Cruz VBM voters mailed in their ballots, by November 2012 that figure was down to 52 percent. The other 48 percent returned their VBM ballots in person in November 2012, with most of those dropped off at a polling place on Election Day.

Sacramento County had a slightly higher percentage of VBM voters using the mail to return their ballots for the November 2012 election, at 59 percent. The large majority of the remaining 41 percent returned them to polling places. Orange County, on the other hand, saw 80 percent of its VBM voters use the mail to return their VBM ballots, with just 19 percent dropping them off at polling places.

Election staff reported that the increasing percentage of ballots arriving close to or on Election Day creates a bigger challenge for agency staff in processing those ballots on a timely basis. The chart below shows the number of VBM ballots Sacramento received on each day prior to the November 6, 2012 election.

Third-Party Return of Vote-by-Mail Ballots

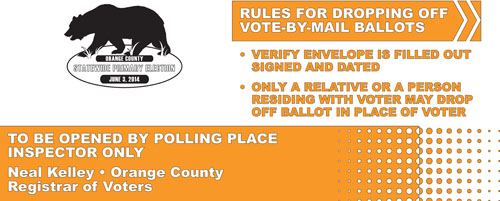

A voter can authorize another individual to return his or her VBM ballot to the Elections Office or polling place if that voter cannot return the ballot him or herself due to illness, disability or being out of town. Individuals eligible to return ballots are limited to a voter’s immediate relative (specifically a spouse, child, parent, grandparent, grandchild, brother or sister) or another member of the voter’s household. A VBM ballot that is returned by a third party other than one of these authorized individuals is invalid, although it appears this provision operates mostly on the honor system. In Orange County, for example, pollworkers do check VBM ballots for signatures and direct third parties returning ballots on someone else’s behalf to review the posted rules but do not ask questions or attempt to verify their relationship to the voter. In all three counties CVF studied, unauthorized return did not show up at all in the data as a reason for ballots not being counted.

All three counties’ ID envelopes include clear language indicating exactly who is eligible to return a voter’s ballot, and all envelopes require the authorized individual’s printed name and signature. Santa Cruz’s and Sacramento’s envelopes specify “illness or other physical disability” as reasons a voter can authorize another individual to return his/her ballot, whereas Orange County’s envelope states simply “I am unable to return my ballot and hereby authorize…” Orange and Santa Cruz counties require the relationship of the third party to be specified, whereas Sacramento does not. (18)

Despite the fact that no ballots in the three counties studied were rejected due to unauthorized third party delivery, one county, Orange, featured a notice on its ID envelope indicating this was among the top four reasons VBM ballots were not counted, though this may be changed for future elections.

|

Orange County added this notice to the vote-by-mail ballot collection boxes located inside polling places to provide additional third-party return instructions to voters. |

At least one county election official agreed that the issue of third party ballot drop off can be an impediment to successful VBM voting, mostly due to third parties delivering VBM ballots that lack the third party’s signature and go unchecked by pollworkers before being dropped in the box. Orange County recently conducted a broad campaign to address this issue, using paid advertising to educate voters about the rules for returning another voter’s ballot. The campaign also included improvements in pollworker training and polling place notifications about the rules. Orange County reported that the additional education has reduced problems relating to unauthorized third party ballot drop off.

13. Signature verification

On average across the three counties examined in this study, a ballot envelope signature that does not compare to the signature on record is the third most common reason vote-by-mail ballots go uncounted. Of all VBM ballots uncounted in the four recent elections studied in Orange, Sacramento and Santa Cruz counties, 18 percent (4,302 total ballots) were invalidated because the VBM voter’s signature did not compare adequately to the one on file with the county.

There is, however, quite a lot of variance between the counties in terms of the number of ballots that are rejected due to signature comparison problems, and that number can even vary significantly within a particular county from election to election.

Orange County on average has by far the lowest rate of uncounted ballots due to signature mismatch of all three counties. Such ballots accounted for just six percent of all uncounted VBM ballots in the county in the four elections studied, although the rate increased from three percent in November 2010 to eight percent in November 2012. In Orange County, a bigger problem by far is VBM ballots coming in with no signature at all.

In Sacramento County, a signature that does not compare adequately is the second most common reason VBM ballots are challenged, accounting for 34 percent of all uncounted VBM ballots in that county during the same four-election period. This high number of ballots rejected for signatures that don't compare contributes to a slightly lower overall success rate for VBM voters in the county (99 percent as compared to the three-county average of 99.2 percent). The percentage of VBM ballots not counted for this reason ranged from a low of 26 percent in November 2010 to a high of 40 percent in November 2012.

In Santa Cruz County, late ballots account for 70 percent of uncounted VBM ballots; the rest are split about evenly between ballot envelopes without signatures and those with signatures that do not compare. While non-matching signatures on average account for 15 percent of invalid VBM ballots in Santa Cruz, that figure has grown over the last four years, from five percent in November 2008 to 19 percent in November 2012.

Guidelines for verifying signatures

One reason there may be large differences from one county to the next in terms of the number of VBM ballots rejected due to signature mismatch is that there are very few uniform standards for what workers who are actually viewing the signatures on the ballot ID envelopes should look for when comparing, and what constitutes a signature that does not compare.

Under current law, counties are required to compare a voter’s signature on a VBM envelope to the signature on their voter registration form or other correspondence with the county election office. But state law, as well as the Secretary of State’s Uniform Vote Counting Standards (19) are both limited when it comes to the matter of what criteria to use to compare signatures.

Current California statute specifies that a voter’s use of an initial for first or last name rather than writing out the full name is not a reason to determine a signature does not compare (Election Code Section 3019(d)). The Uniform Vote Counting Standards describe several vote-by-mail signature irregularities and say what counties should do in each situation. But neither the standards nor the statute provide any guidance for counties for the criteria to use to actually compare a voter’s VBM envelope signature to a signature or signatures on file.

All three counties' have written signature verification guidelines which have a few things in common, including directing workers to consider: the slant of the handwriting; how letters are connected; how "t"s are crossed and "i"s are dotted; and whether initials are substituted for any part of a signature (and what to do about that). (20)

Unique to Santa Cruz County's signature verification guidelines are the following: the instruction to turn the signature on the ID envelope upside down to see if there is a similarity; the instruction to compare the printing on the voter registration card and ID envelope; and, an explanation of what to do if the signature compares to the signature of a voter's spouse.

Unique to Orange County's signature verification guidelines are the following: the instruction to look at similarities in the formation of the letters "F", "G", "Y", or "Z", and the shape of cursive loops; and, information about what to do if only part of the signature is there, a signature includes middle and last names but no first name, or a signature is for a married/maiden name.

Orange County uses the language, "There may be variations on a voter's signature" but does not specifically state in its signature verification guidelines that signatures don't have to be an exact "match". Both Sacramento and Santa Cruz counties’ guidelines include the clear statements that "The operative word is compare" and "The signatures do not have to be an exact match."

Santa Cruz County election officials report that their staff tries to match three points – slant, curve, swish – when comparing signatures, but the guidelines don't specifically mention that. Staff also utilize the “three second rule”: if an election worker looks at a signature for longer than three seconds, that is reason enough to take a closer look and that ballot envelope is set aside for a supervisor to review. Santa Cruz election workers once received training from the Sheriff's office that taught them to look at pen marks and the impression of a pen, but those topics are not included in the written guidelines for checking signatures. (It is possible those techniques are used only by supervisors who are reviewing ballots that have been initially challenged for signature non-comparison.)

Like Santa Cruz, Orange County has also consulted with a local sheriff's department to receive additional training and advice about signature verification. Orange County invited representatives from the Los Angeles Sheriff’s office to come and teach them more about how to verify signatures. The consultation changed the signature comparison process in Orange County and resulted in more VBM ballots being rejected because of mismatching signatures. Though the L.A. Sheriff's office staff do not continue to come to Orange County each election, the election office does have one of their own staff members teach a class to all election workers who participate in signature verification, which draws from the Sheriff Office’s training.

Process for handling signatures that don't compare

Counties have slightly different processes for handling situations in which an election worker determines a voter's signature may not compare.

In Sacramento, ballots challenged for reasons of signature mismatch are reviewed by permanent election office staff, or in the event seasoned staff cannot make a determination, by the Registrar and Assistant Registrar. Ballot envelopes with signatures that do not show any similarities to the one on record are marked with a "Challenged" stamp and entered into the database as challenged. Election staff members do attempt to locate the ballots of any other voter in the household who may have used their housemate's envelope by mistake, but this practice is not addressed in Sacramento's written signature verification guidelines. Voters whose ballots are challenged due to a signature that doesn't compare are not contacted until after the election.

In Santa Cruz, workers write "Sig" on the ballot ID envelope along with their own initials, and then place the ballot in a challenge box. All such ballots are then reviewed by a supervisor, who makes the final decision regarding the signature. If a signature is found not to compare, Santa Cruz attempts to contact the voter before the end of Election Day, to give him or her the opportunity to cast a valid ballot.

Regarding spouses signing each other’s envelopes, Santa Cruz County's "How to Check Signatures" guidelines state this invalidates the ballot; however, in interviews conducted for this study, county staff said there was no harm of a spouse using the other spouse’s envelope as long as both ballots and both envelopes come back. If spouses return their ballots in each others' envelopes, election staff will count them if both are returned.

Orange County's signature verification guidelines simply state "If the ROV staff determines that the signature of the voter does not have any similarity to the signature on the original affidavit of registration, the ballot is not counted." Ballots are then marked in the database as "Challenged" and "Non-Matching Signature."

Reasons why signatures don’t compare

The reasons for signatures not comparing are numerous. Peoples’ signatures can change over time. If a voter registered to vote and does not re-register, and their signature changes through the years, it may no longer sufficiently compare to the signature on file with the county. In 2013, the California Legislature enacted a new law that allows registrars to use, in addition to the most recent voter registration application signature, signatures from other documents on file, such as a vote-by-mail ballot request or an older voter registration signature, to verify VBM envelope signatures, giving county election officials additional tools for signature verification. (21)

Another issue that all counties increasingly have to confront is signatures made with a stylus rather than a pen. Through the Secretary of State’s online voter registration system, voters register online using their signatures on file with the Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV), which are sometimes made with a stylus. These signatures get forwarded to the counties to use when verifying VBM ballots and for other election security purposes such as verifying provisional ballots and initiative petitions. Sometimes they have a thick, fuzzy quality and are referred to as “Sharpie” signatures. As use of this signing technology proliferates, counties may have more difficulty comparing these signatures than those made with a regular pen.

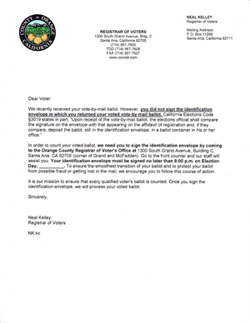

The most common reason signatures don’t match, according to the three registrars interviewed, is because a family member has signed a ballot envelope on behalf of another family member, typically a spouse or child. In Santa Cruz County, when a signature does not match the first thing election staff do is examine the signatures on file for other voters in the same household. When signatures don’t match, all three counties contact the voters by mail to attempt to collect a new signature. Incidents of apparent attempted election fraud are rare and, if detected, are reported to the Secretary of State or the local district attorney.

14. Automation

|

With about twice as many voters, Orange County's vote-by-mail processing equipment is about twice as long as Sacramento's. |

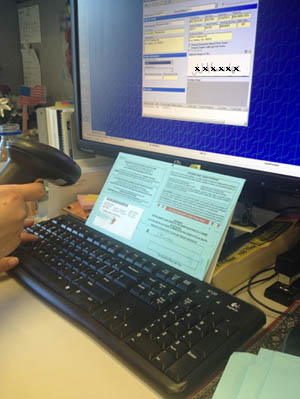

California counties have automated the vote-by-mail ballot counting process in varying degrees. Smaller counties typically deploy a manual process, using employees to sort, open and verify VBM ballot envelopes. Larger counties use machines to automate the ballot sorting, opening and, in some cases, signature verification. In many counties, it is a mix of manual and automated processing. In Sacramento and Orange Counties, for example, a hybrid system is used: both counties use machines and software to scan the ID envelope barcodes in order to sort ballots into their proper precincts. With about twice as many VBM voters as Sacramento, Orange County’s ballot sorting machine is about twice as long. Sacramento and Orange use technology to scan and store an image of the envelope signature.

Equipment is also used to open VBM envelopes and separate ballots from the envelopes. Actual signature verification, however, is performed by an election staff member who makes a side-by-side visual comparison on a computer screen for each ballot of the image of the envelope signature and an image of the voter’s registration application signature.

|

Sacramento County's vote-by-mail processing equipment sorts ballot envelopes from the June 2014 primary election. |

Santa Cruz has handled the VBM ballot counting process almost entirely manually. Ballots are sorted by election staff into precincts by hand, opened by hand with a letter opener, and a simple tally sheet is used to track the number of ballots arriving for each precinct each day. An election staff member uses a handheld scanner to read barcodes on the VBM ID envelope in order to call up the voter’s record and signature image on a computer screen and then visually compare it to the signature on the VBM envelope.

However, the county is planning to move to an automated process for ballot sorting, opening and verification and has already acquired the equipment to do so. The automated signature verification will use software to compare the voter’s VBM envelope signature to their registration signature. The decision to move to an automated system was made after the November 2012 election, when the registrar’s office had to hire temporary workers, get help from staff in other county departments, and use additional rooms in the county building in order to manually process the high volume of VBM ballots that were returned. For Santa Cruz, automation will free up staff, though not necessarily speed up the process since any ballot rejected will reportedly need to be reviewed by a person.

|

A Santa Cruz County election worker uses a hand-held scanner to scan a vote-by-mail envelope bar code to call up the voter's record and signature image on a computer screen for comparison. |

Santa Cruz joins several other California counties, including the largest, Los Angeles, in using commercial products to scan, compare and verify the signatures on VBM envelopes. Currently the use of these products is unregulated and uncertified, making it possible for counties to set the parameters for accepting or rejecting signatures at varying tolerances. There also are no guidelines or best practices provided by the Secretary of State to help counties ensure they are properly deploying automated signature verification technology.

According to Santa Cruz County's Clerk, Gail Pellerin, the county plans to set the new equipment's automated signature verification thresholds strictly, which will lead to more ballots needing to be reviewed by staff, but will also avoid erroneously accepting ballots in which the signature does not adequately compare.